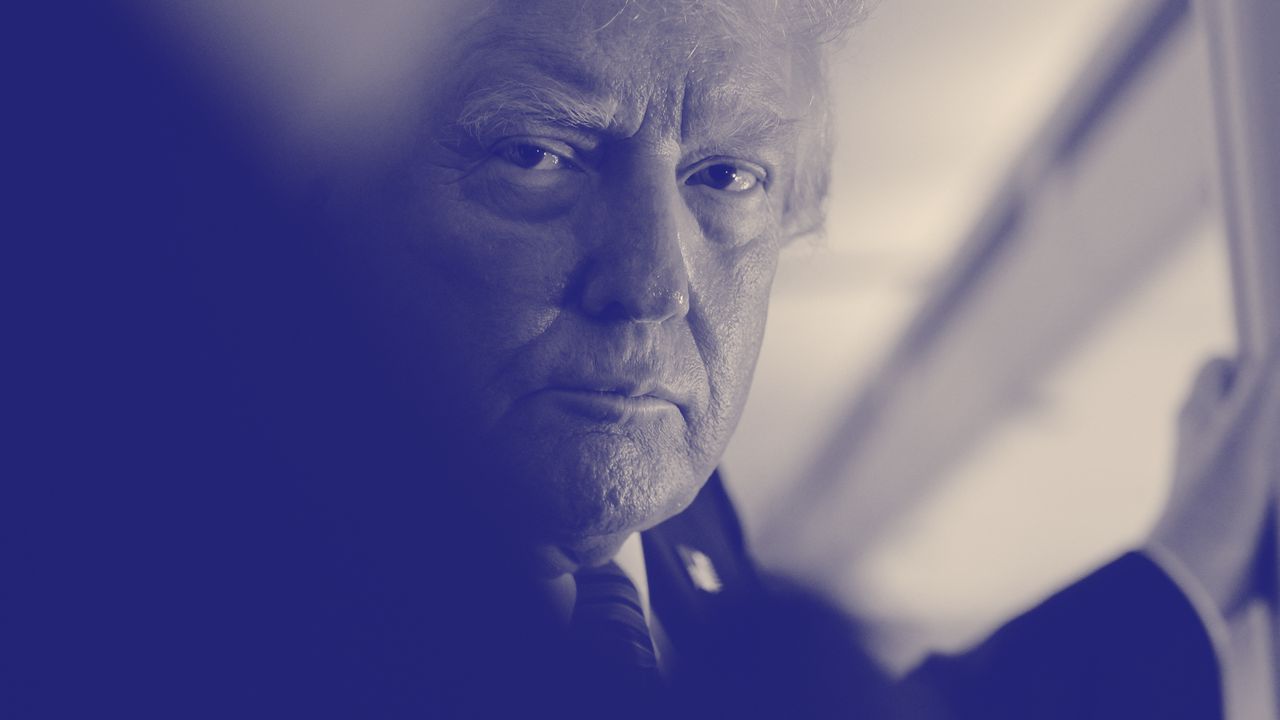

In the past several weeks, President Donald Trump, who has never been fastidious about separating public and private business, has been involved in a remarkable number of potential conflicts of interest. He recently announced his intention to accept a four-hundred-million-dollar Boeing 747 from the Qatari government, which would be used in lieu of Air Force One for the remainder of his Presidency, after which it would be transferred to his Presidential library; he has continued selling access to himself through his meme coin (a company with ties to China recently announced that it would buy as much as three hundred million dollars’ worth of the coin, $TRUMP); and his trip to Saudi Arabia this week was preceded by his family’s announcement, late last year, of a new Trump Tower Jeddah. The scale of these conflicts may be unique for an American politician, but Trump, who has consistently condemned the Washington “swamp,” is one of many right-wing “populist” leaders and former leaders —Viktor Orbán, of Hungary; Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, of Turkey; Narendra Modi, of India; Jair Bolsonaro, the former President of Brazil—who have won election by running against a supposedly corrupt system, and then become embroiled in corruption scandals that often vastly eclipse those of their predecessors.

To talk about corruption, and its relationship to contemporary right-wing populism, I recently spoke by phone with Kim Lane Scheppele, a professor of sociology and international affairs at Princeton. Scheppele studies the ways in which democratic institutions come under threat—from individual politicians and from events, such as economic crashes, or in response to terrorism. During our conversation, which has been edited for length and clarity, we discussed why Trump’s corruption is distinct from those of his ideological brethren, why autocrats become surrounded with other corrupt people, and how corruption has been turned into a culture-war issue.

The relationship between corruption and the modern incarnation of right-wing populism is twofold, in that populists often run against corruption and then behave corruptly. Is that a coincidence, or are those two things connected?

There is certainly a connection between autocracy and corruption. There’s also a connection between corruption and all kinds of other things, so autocracy is not the only cause. But if a leader comes to power and starts eliminating all checks on the executive, one set of those checks will be the kinds of things that can detect and control corruption. It’s very often the case that autocrats who want to stay in power forever think, Well, gee, as long as I’m here, why don’t I just grab everything in sight? It’s a pretty common pattern that autocrats, sooner or later, engage in self-enrichment as part of their power grab.

How do you understand the fact that so many of these figures gained power by campaigning against corruption?

A lot of autocrats run on anti-corruption platforms, but often what they actually do is change the kind of corruption that exists. The kind of corruption that we saw in post-Communist Europe, for example, was a kind of corruption where all the state employees were underpaid. They weren’t entirely sure they wanted to be there. So, if you really needed to get something from the state, such as a permit, or a license, or even a passport, you’d go to the office and the clerk would tell you to stick something in his pocket and then he would make it happen. It was that kind of visible, street-level corruption.

When Vladimir Putin came to power, in Russia, or when Orbán came to power, in Hungary, they cracked down on a lot of that kind of corruption. They were really good at punishing street-level bureaucrats for engaging in it. And, in exchange, they substituted a different kind of corruption, which was skimming off the top of state contracts and seeking favors or seeking rewards from people who needed something from the very top of the system. That kind of corruption, where you give state contracts to your friends in exchange for taking something off the top, is not very visible to the average person. And so it’s often the case that when those kinds of autocrats come to power, it looks like they’re stamping out corruption, and they are stamping out a particular kind of corruption, but they’re moving it elsewhere in the system, where it’s not so visible. So, it’s not surprising that autocrats typically run on anti-corruption platforms. And it is not surprising that their fans think they’ve actually fought corruption in some kind of meaningful way. But it’s not inconsistent with the idea that these autocrats are also corrupt. They are just corrupt differently.

I don’t want to draw exact parallels, but it reminds me of how Trump and Elon Musk are talking about the U.S. government now, saying it’s wasteful, it’s inefficient, it’s giving all your money to people that don’t deserve it. I’m skeptical that Trump is actually going to be successful in stopping whatever corruption of this sort actually exists, but clearly what it’s going to be replaced with is a type of oligarchy where Trump and his friends take from the top, as you were explaining.

Exactly. They are saying that Social Security pays people who are a hundred and fifty years old, or that Medicaid is going to undeserving people who are just malingering. And they claim to see a lot of corruption in the kinds of welfare programs that the state runs. And that’s something that has a very broad audience because, first of all, there probably is a lot of low-scale fiddling with the rules. Many people probably know somebody who’s gotten a state benefit that they didn’t entirely deserve. And so that kind of corruption looks like something that does have to be wiped out. But then what you get instead is a budget going through Congress that would massively tilt tax benefits toward Trump and Musk. Also, if you look at Elon Musk, his fortune is largely from a basis in what were state contracts. And there have been reports about making the Federal Aviation Administration use Starlink, which he owns, or about firing the people who were investigating his companies. So Musk stands to get massively more wealthy from exactly what he’s doing in his government capacity. But this corruption might not be as visible as the street-level stuff that people feel familiar with.

What is striking about Trump is how openly corrupt he is in other ways. Does that make him distinct from other leaders?

Yeah, but I think that this kind of corruption is consistent with Trump’s brand. He’s known as a successful businessman. Whether he is or not is a different question. But that’s the reputation. And he’s made a career out of taking advantage of opportunities, or, at least, this is the way he portrays it, and that that’s part of what makes him successful. So the openness of the corruption is partly just a flouting of all the rules, for which he gets a lot of credit with his base anyway. Some of it is also building on the brand that somebody really smart will take advantage of whatever opportunity is presented to them.

Now, that’s really different from someone like Orbán or someone like Putin. They came to power as anti-corruption figures determined to turn around economies that had basically collapsed. They couldn’t be seen to be skimming off the top. So what happens in Hungary is that very little of Orbán’s fortune is held in Orbán’s name. Instead, his friend from school, a guy whose name is Lőrinc Mészáros, who was a manual worker, has now become the richest man in Hungary. How has he become rich? He’s become rich off of state contracts, and his nickname is Orban’s Walking Wallet. He’s the thing into which Orbán sticks his cash. It is not in Orbán’s name. He goes to great lengths to hide the wealth that he’s accumulating by virtue of being an autocrat.

Putin is much the same. He has these villas that drones have discovered, and a lot of offshore wealth, which is really hard to document because of the complex way in which it’s kept. But these autocrats’ corruption is hidden because it’s not consistent with their brand. So, I think it varies, but Trump is really one of a kind in the sense of being so out in the open about violating all the ethics rules that this government has.

Trump is arguing that the system is corrupt and rigged, but he’s essentially saying, reading both between the lines and not between the lines, that it’s rigged in favor of other people. And these other people tend not to be his base. So I’m curious about the degree to which that’s true in the countries you’ve studied—that it becomes hard to separate out corruption as a rhetorical issue from other cultural issues or resentments.

I think this is absolutely true in India, and to some extent in the U.S., where the corruption narrative is that there are all these undeserving people who are getting stuff that you should be getting. And that I, the leader, will redirect that stuff to you. Another thing about Modi, though, is that his whole brand is to look pious, and to look like he’s the kind of man for whom money is the least important thing in life. So it would be completely scandalous to discover that he’s skimming money off the top.

Right, and what’s happened in India in the last decade under Modi—at least that we know about—is that billionaires close to Modi have become extremely well off, in part through the government. It’s not that there are lots of reports of Modi being personally corrupt.

Right, but it’s interesting that that was Putin’s reputation for the first decade, too—that he was very disciplined, that he doesn’t really drink, he doesn’t do anything to excess. He’s this kind of austere figure. And that was what made him so popular in Russia. And now, of course, it also seems that he’s skimming money off the top and stashing it overseas. But it’s extremely hard to document that. So I guess the major point I’m making here is that how corruption manifests itself in any particular autocratizing regime will depend on what the autocrat’s brand is and what their relationship is to money. If Trump has said that money is the ultimate value, and that he has more of it than anybody else, then anything that makes that money grow looks like he’s capitalizing on what he promised.

There also seems to be something about people who are already corrupt entrenching themselves in anti-establishment right-wing politics. I think, with Trump, the corruption predated his political views. And a lot of the corrupt people around Trump need to wind up with someone like him, who himself is corrupt, because the system goes after people who are corrupt.

It’s true. Corruption and autocracies involve removing all the rules that allowed the system to function in a more or less integrity-based manner. Part of that’s conflict-of-interest rules, part of that’s oversight. Part of what we’re seeing now in America is the firing of people who would engage in oversight and regulation of the billionaires’ fortunes. That’s pretty obvious. But it’s also the case that, when autocratic governments come into power, one of the first things they do is accuse their opponents of corruption and launch corruption investigations against other people. So, if you remember, Trump, in 2019, tried to get the then relatively unknown Volodymyr Zelensky to open an investigation into the Biden family. The point wasn’t just to convict them of anything. The point was to throw mud on them. Trump accuses Biden of being corrupt, and then Biden turns around and says, “No, you’re corrupt.” It sounds like it’s in a playground: “You started it.” “No, you started it.” And when that kind of thing happens, people who are listening just discount both sides. Accusing your opponents of corruption when you yourself are corrupt, even in the absence of any actual corruption on the part of your opponent, generates an audience tune-out. People say they don’t know who is more corrupt and ignore it all.

But this isn’t just the result of populist politicians. Saying the system is broken and corrupt, and that Washington is a swamp—these are widespread opinions that mainstream figures of both parties have said in broad terms, forever. And I understand that they don’t mean it in the way Trump means it. But we’re in a pretty cynical time, and have been for a while, and, if you asked someone a decade ago about Washington politicians, you would have heard they were all crooks.

I think that’s true. Corruption is an all-purpose accusation that can be applied in many different kinds of contexts. So when you get an autocrat that hides their corruption behind accusations of corruption on the part of others, it doesn’t look that different from ordinary politics. And that’s exactly one of the things that justifies it.

China is not just autocratizing but a malign dictatorship. One thing you see in China, which you see in lesser degrees in other countries, is that, when Xi Jinping was trying to consolidate his own power there and erase all the little bits of freedom and light in the system, he accused all of his opponents of corruption. He launched this big drive called the “tigers and flies” drive. “Tigers” meaning he would bring down major public figures, and “flies” meaning all the little people engaged in corruption. And this anti-corruption drive, which was absolutely massive and went on for some time, was how Xi purged the Party to make way for him to essentially declare himself President for life. So autocrats don’t just create corruption to benefit themselves but they also use corruption as a really serious weapon against their enemies. And it can be part of the consolidation of their power that they use anti-corruption measures in that way.

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the part of the federal government that Trump has had the most ire toward is the Department of Justice. When you’re a crook, the Department of Justice will likely come after you. It was coming after him in a certain way in the first term, and it was certainly coming after him during the Biden Presidency. Some people use this to say, “Well, they should have never tried Trump on January 6th” or whatever else, which I don’t think is a convincing argument at all. But it does become a situation where leaders like Trump end up going harder at the system.

Absolutely. One of the first things that somebody who really wants to be corrupt does is to corrupt the prosecutor, because they’re exactly who would enforce the law against them. When Orbán came to power, one of his first appointees was his loyal friend Péter Polt as the country’s chief prosecutor. And Polt was prosecutor for fifteen years, ignoring all the corruption on the Orbán side and going after corruption and all kinds of minor offenses on the other side.

Right, and just to go back to the thing I was saying earlier about who you surround yourself with, I was thinking that in two years I could see Eric Adams, the Mayor of New York City, getting a cabinet appointment.

Might be one year.

This would have been hard to explain to someone a couple years ago, but the reason is just that Adams had a corruption case against him and, to get out of it, needed to turn to Trump. It becomes a cycle that has made and will make the MAGA movement more and more corrupt.

If you look around the world at autocrats, they divide into multiple camps. There are some, like Modi or like the former Polish leader Jaroslaw Kaczyński for example, who actually believe their own line, I think, which is to say they are kind of ideologically driven toward a particular goal. And with Kaczyński, in Poland, and Modi, in India, there are religious goals to make or remake the whole society as a kind of religious paradise, so to speak. These are the autocrats who are less likely to engage in personal corruption, because they believe in something.

But then there are these sort of opportunistic autocrats, like Orbán, like Putin, like Trump. It’s very hard to say what they stand for. They change their minds. One day they’re in favor of this, the next day they’re in favor of that. And I think that’s partly because they don’t have a solid ideological grounding—they’re in it for the personal benefit, and they’re in it for the immunity they get by virtue of holding the office. If that’s the case, then they need to surround themselves with people who are not going to blow the whistle on them, because, just as they neutralize the prosecutor and the tax authorities, they also need to neutralize all the potential whistle-blowers. They want to have people in those inner-circle meetings who have the same kind of stake in the system that they do. And if these other people are willing to go along with the corruption, well, that’s exactly who they want, because they have something on those folks as well as those folks having something on them. It’s a kind of mutual-assurance pact. And this is a kind of discipline that holds the whole thing together. That’s how some states are organizing themselves now. ♦