Just before 11 P.M. this past December 3rd, the Korean legislator Lee Jae-myung issued a dire warning from a moving car. “My fellow-Koreans, you must come out to the National Assembly,” he said, in a live stream from his phone. The video showed Lee in a dark suit and a royal-blue tie, the color of his Democratic Party. He looked weary and frightened. “Our democracy is collapsing,” he said. “Please come together to protect it.”

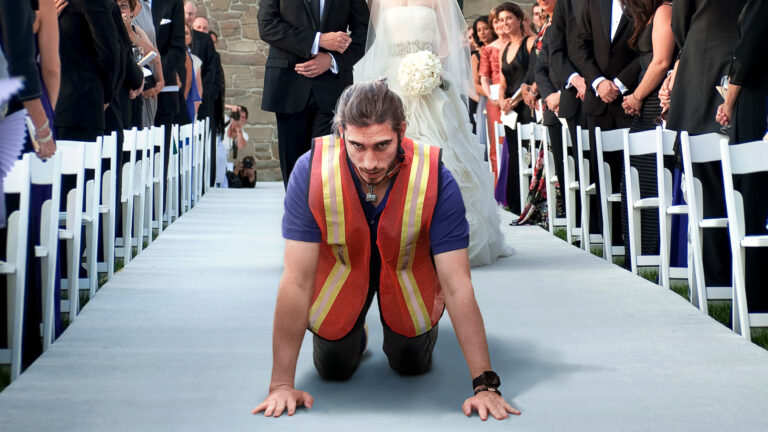

The nation’s President, Yoon Suk-yeol, who was a prosecutor before being groomed for leadership by the People Power Party, had spent the past few years turning the machinery of the state against political opponents, trade unions, and journalists who criticized him. Now he had declared martial law and sent troops to lock down the parliamentary complex. But Lee and his allies hoped that they could prevail: because of South Korea’s recent history of military dictatorships, its constitution allows the legislature to constrain orders of martial law. The night that Lee issued his call, thousands of citizens showed up at the National Assembly. They helped Democratic Party legislators, and even a few conservatives typically aligned with Yoon, make their way past the soldiers and break into the building to vote down the order. It was an uncommon instance of coöperation across party lines in extreme circumstances—and, I argued at the time, a model for fighting authoritarianism elsewhere.

A great deal has happened since. From December through April, there were ecstatic daily protests, demanding that Yoon be ousted. These were followed by Yoon’s impeachment by the National Assembly, his criminal indictment, his formal removal by the Constitutional Court—and, this Tuesday, a snap election to replace him. In the 2022 Presidential election, Lee lost to Yoon by less than one per cent. This time, he won by more than eight points. He will be inaugurated on Wednesday, beginning a five-year term.

Lee is sixty-one years old, a scrapper with a potent backstory. He grew up in poverty, in the eastern part of the country, and got a job instead of attending middle school; his left arm was later crushed in a factory accident, causing it to splay at the elbow. He went on to become a human-rights lawyer, a mayor, and the governor of Korea’s most populous province. He has pushed redistributive policies, including universal basic income, while sticking to the Democratic mainstream. He is pro-development and pro-welfare state, loyal to the United States but respectably independent. Last year, he survived an assassination attempt at a public appearance: a man in his sixties, posing as a supporter and wearing a paper crown that read “I am Lee Jae-myung,” plunged a knife into his neck. The attacker had written a screed saying that he intended to save Korea from “left-wing forces.”

Lee has been involved in numerous controversies. In the early two-thousands, he was found to have misrepresented himself as a prosecutor to help a journalist investigate a mayor suspected of corruption; he was accused of having an extramarital affair; his son reportedly posted misogynistic comments online. He has faced multiple prosecutions, including one for lying about his relationship to a real-estate developer during an election debate, in 2021. (Korea strictly regulates election-related speech; that case was appealed and is on hold.) The episodes provoked criticism that was often tinged with classist disdain; conservatives described Lee as a “petty criminal” who swims in “dirty waters.” But a liberal friend also surprised me by writing him off as “dangerous” and “too messy” to run the country. Far-right and evangelical groups targeted him for his views, labelling him a “pinko commie” and organizing campaigns to smear him online.

In the recent election, Lee’s main rival was Kim Moon-soo, a former labor minister who served as Yoon’s proxy. Kim is not a dynamic presence, but he upheld the party line. In one of three debates, he called Lee the country’s “most corrupt government official.” He argued that Yoon had been driven to declare martial law because Lee and the rest of the Democratic Party had repeatedly blocked legislation in the National Assembly. The People Power Party downplayed the attempted self-coup as a silly misstep. “There was quick action to lift the martial law, and it got lifted, didn’t it?” Kim said in the final debate.

I travelled around Korea in the days leading up to the election. In Cheonan, one of Kim’s campaign trucks blared music, while a surrogate shouted slogans through a muffled P.A. system. In Namyangju, a city in the province where Lee was governor, banners read, “A vote in this election is a win for the people” and “Cast your vote to stop the treason!” Early voters in Seoul took selfies outside a polling station; there were long lines and lots of buzz, mostly in Lee’s favor.

Nearly eighty per cent of eligible voters turned out—Election Day was a national holiday—but at the polls I visited the mood was subdued. I kept thinking about two other recent elections. The first was the Korean snap election in 2017, to replace President Park Geun-hye. Its contours were nearly identical to this year’s: misconduct by a conservative President, months of mass protests, impeachment, removal, criminal prosecution, and the election of a liberal replacement—Moon Jae-in, who, like Lee, had been a human-rights lawyer. The second was the U.S. election of 2020, which Joe Biden framed as a plebiscite on a dangerously venal leader, and which came just after that year’s Black Lives Matter demonstrations, the largest in American history. Both Moon and Biden campaigned on who they were not—presenting themselves as antidotes or correctives—while promising not to forget the social movements that brought them to power. Both ended up struggling to hold their country together, let alone effect the changes that their activist supporters had hoped to see.

What will come of the resistance to Yoon? The movement—large, diverse, and energetic—was largely sustained by young women, who waved “Impeach Yoon” signs to the beat of K-pop and adapted flashing L.E.D. batons, concertgoers’ accessories, to the purpose of ousting a would-be autocrat. Yoon had made women-bashing a core principle. As a candidate and as President, he had fixated on abolishing South Korea’s gender ministry, and implied that feminism was the cause of many social ills, such as overpriced housing, underemployment among young men, and a record-low fertility rate. He surrounded himself with military generals. In a different world, the Democratic Party would have chosen a woman—perhaps a member of the National Assembly, which is about one-fifth female—to run for President to succeed Yoon, pushing for an omnibus anti-discrimination law that has been a perennial goal of women and minority groups.

Instead, Lee largely avoided questions of gender during the campaign, and made no particular appeal to the labor movement or to poor people, constituencies he had previously courted. Determined not to alienate all of Yoon’s supporters, he called himself a “real conservative”—as distinct from the radicals who would institute martial law. Yet, as polls showed him taking a comfortable lead, Lee began to sound more like his old self. “Do you know why they’re against Lee Jae-myung?” he said to a crowd in Cheongju last weekend, referring to himself in the third person. “It’s because Lee Jae-myung is from the periphery. He’s on the side of small and medium-sized businesses, not big corporations. He stands with the poor and working class.”

Lee wants to go beyond correcting Yoon’s strongman Presidency. But his victory feels more like a reassertion of reality than a referendum on the values of either major party. It is a vote against Yoon and others who would embrace a return to the military dictatorships of the nineteen-seventies and eighties. “Finally, that day of martial law is over,” said a man who celebrated the results in front of the National Assembly, to the news site Pressian.

In office, Lee must contend with an unenviable pile of problems. Though some seventeen million voters got behind him, there is no consensus; the nation is split—by gender, class, and geography—and recovering from a prolonged political trauma, including multiple Presidential impeachments and prosecutions. The other, historic split, from North Korea, continues to inspire an arms buildup and a lingering paranoia over Communism. South Korea’s unemployment rate is around three per cent, but higher for younger workers. About half of the population lives in greater Seoul, for lack of jobs in the provinces. Outside Lee’s campaign headquarters, I attended a rally meant to highlight the precarious conditions of temporary and subcontracted employees; a few days later, a subcontracted worker died in a lathe accident at a power plant that was known to be unsafe. The auto and semiconductor industries, which together supplied more than thirty per cent of Korea’s exports in 2024, have been stunned by Donald Trump’s whipsawing tariffs.

Still, Lee has reason to feel optimistic. His win is the sign of a functioning democracy and a refutation of authoritarianism. Late last night, on a stage near the National Assembly, he raised his good arm and pumped a fist to the chants of the crowd. “The people are the masters of this country,” he said. “The President’s job is to bring the people together.” ♦